It’s been over two years since Carl Trueman published the book, The Rise and Triumph of the Modern Self. People are still talking about it, which for our society suggests a longer shelf life than most publications. At 432 pages it’s intimidating, but the reason it remains under discussion is that Trueman forthrightly engages with our society’s obsession with sexual identity. It seems our students are locked in rooms where the most important thing to be talked about is “who” one is – man, woman, binary, cisgender, LGBTQ++.

This article is not about those things exactly; rather, I’m interested in Trueman’s analysis of what’s driving the conversation. Building on the works of Philip Reiff (The Triumph of the Therapeutic, 1966) and Charles Taylor (A Secular Age, 2007), he maintains that we have entered into an age of “psychological man” in which people find their identity in inward quest for personal psychological acceptance, affirmation and happiness. It’s not just a self-help search. It’s a way of thinking that has become so fundamental that it has become a governing framework, running in the background like an operating system in a computer. Far from being limited to academia, it has been popularized powerfully by media, political parties, and corporate and entertainment conglomerates, and adopted uncritically by school boards across America including the places we live. One could summarize it this way:

— The triumph of the individual as self-referential: One needs nothing from outside to define individuality or the world;

— The rejection of all external authority, especially the Christian Scriptures;

— The individual is the maker of meaning: nothing has meaning beyond what one gives to it or accepts on his own judgment;

— So-called “objective” truths are at best mere constructs, and at worst are constructs designed by the powerful to harm the weak.

Taken together these assumptions issue in an “expressive individualism” which not only shuns external authority, but also carries a resistance to common practices and common liturgies, both of which are expressions of culture that are designed to inform habits of the heart and habits of behavior. It powerfully undermines common moral obligations and the sensibilities that come with it, such as respect for others, reverence, and adherence to community standards.

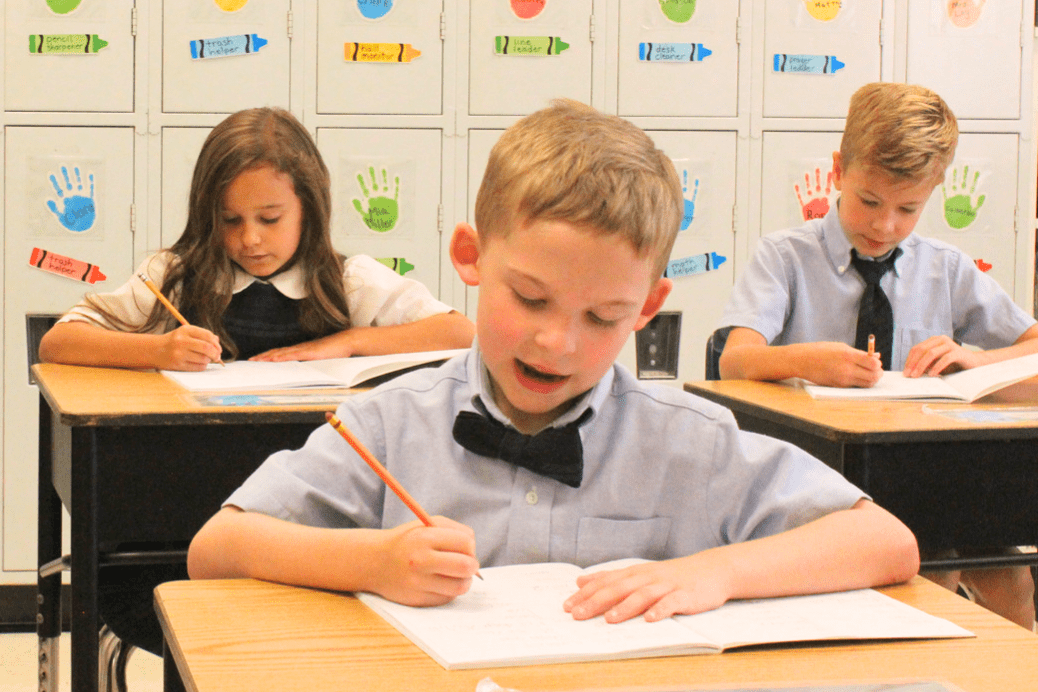

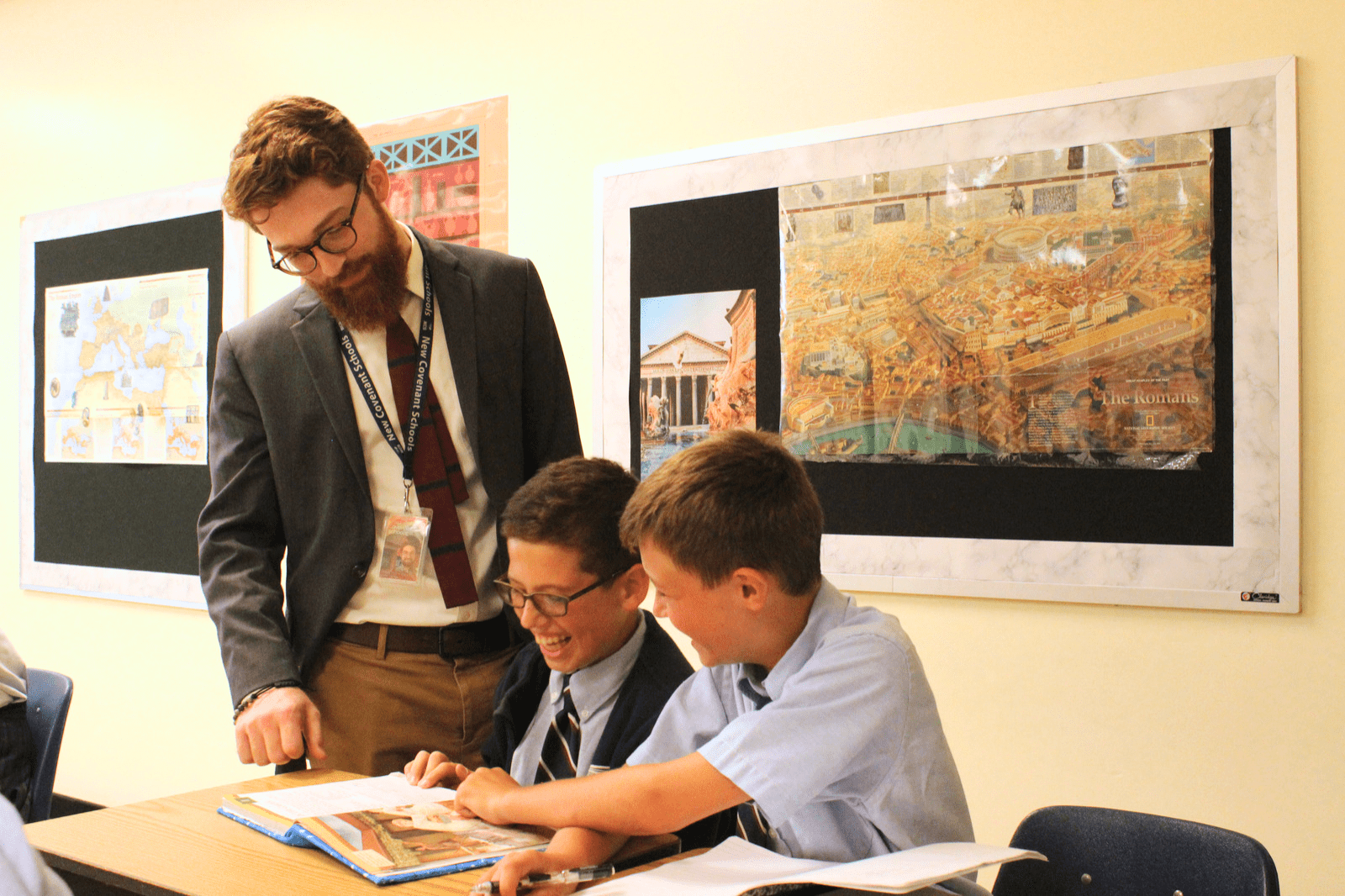

This is what culture does. Culture directs an individual outward. In communal activities individuals find their true selves, which is given and learned. Culture provides the community wherein the individual finds self-consciousness in being recognized by that society. This occurs because one behaves according to the conventions of that society. The expressive individual is at one with the expressive community. A culture’s viability turns on the authority of those institutions that enforce or inculcate norms and communicate them from one generation to another. This is precisely what classical, Christian education purports to do.

For the expressive individual, however, Trueman notes that “institutions cease to be places for the formation of individuals via their schooling in the various practices and disciplines that allow them to take their place in society. Instead they become platforms of performance, where individuals are allowed to be their authentic selves precisely because they are able to give expression to who they are “inside.” He goes on, “In the world of psychological man…the commitment is first and foremost to the self and is inwardly directed. Thus, the order is reversed. Outward institutions become in effect the servants of the individual and a sense of inner well-being” (49).

The reason we find ourselves unable to speak with civility in political discourse, the reason that discussions are so acrimonious and futile, is that there is no longer a commonly accepted foundation on which such discussions might constructively take place. We have not only hardened into polarized political parties; we have hardened into polarized sovereign individuals. The great challenge for our community is to strengthen our family and school cultures, to seek to be self-aware of how our own health is affected by such social viruses. Accomplishing that means that we reject a sanctimonious response in which we see ourselves as somehow standing apart. It means that we recognize and affirm that the triumph of the self is at bottom a quest for dignity. The argument is over where the dignity is sourced. It also entails that we maintain the very heart of our mission: to invigorate the authority, liturgies, practices, moral obligations, and the things we honor in our cultural inheritance. Thus we structure the curriculum and culture of the school to actively advocate an authentic Christian, educational community which the students are asked to respect, and in which they are asked to participate.