The Centers for Disease Control statistics show that about 10% of all children under age 18 have been diagnosed with Attention Deficit Disorder or ADD. Even more children in the same age group meet some or most of the symptomatic criteria of for ADD, though they may not be formally diagnosed. It is so common that new parents don’t need in-service on it—they know that they themselves, along with about half the kids in their own grade school were either labeled with the diagnosis, or could have been.

It should come as no surprise that my colleagues and I routinely address the matter with families at New Covenant. My friend, Keith McCurdy, the President of Total Life Counseling, Inc., in Roanoke, who is a Licensed Professional Counselor and Licensed Marriage and Family Therapist, treats it also. I’ve known Keith for more than fifteen years and have found him to be a master at helping families build sturdy children. Recently, he and I had a conversation about ADD in young people. (Disclaimer: this article is not intended as medical advice or as a criticism to professionals who diagnose or prescribe ADD medication).

There is no clear research to explain the underlying causes of the grab-bag of symptoms associated with ADD; inattention, fidgeting, lack of focus, or acting with without thinking. In order to diagnose ADD, professionals rely on interviews and checklists filled out by teachers and parents which identify troublesome behaviors related to focus and attention. Thus, ADD is not diagnosed with a blood test or other medical procedure.

There is research, however, on various pharmaceuticals that can mitigate or eliminate the symptoms. Keith is quick to warn that, “faced with a ‘grab bag’ of symptoms, we are being asked to prescribe drugs, the side-effects of which are not always fully known, and whose effectiveness may be less than 50%.” He reports that pediatricians refer hundreds of youngsters to him for counsel on student behavior in school, so he sees a lot of kids. Before considering medication, here is how he proceeds.

The first thing he tells parents is, “We need to baseline your child.” This means that before we consider using a drug, we need to get a child functioning biologically as normally as possible. A child’s body wants to function in keeping with how it’s designed, and to allow it to do that, we must make sure that we aren’t getting in the way. There is a three-month behavioral regimen we follow to move toward optimal function.

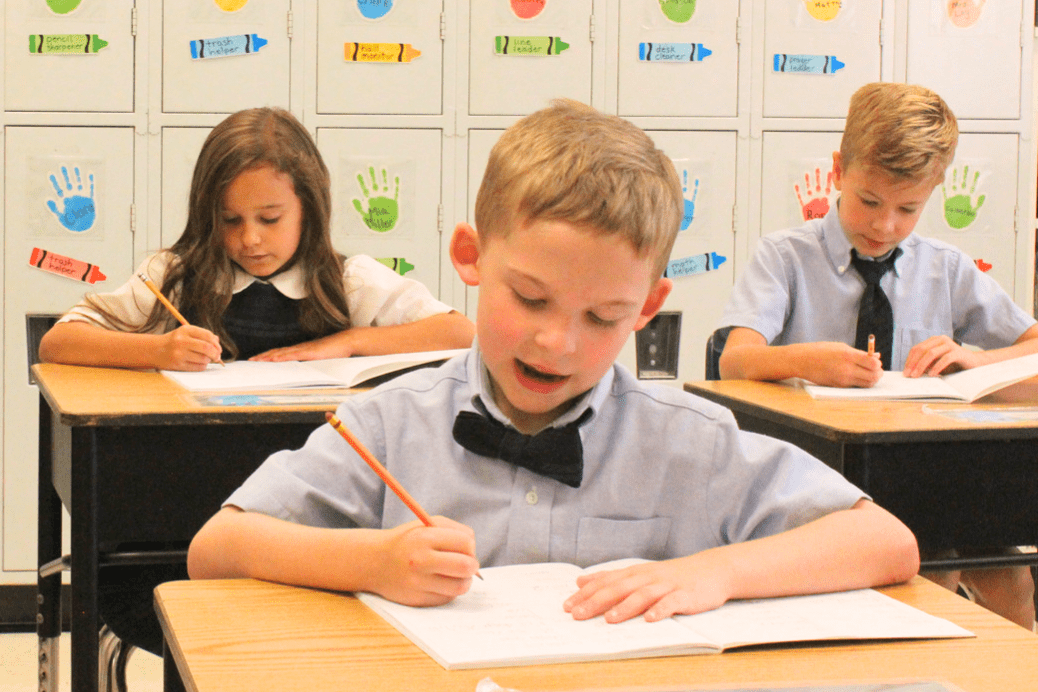

First, eliminate all use of video games, tablets, and phone exposure. There is plenty of research that points to the negative effects of back-lit devices, video graphics, and sustained use of social media platforms on brain development and function. These exposures disturb everything from attention spans to sleep patterns.

Second, put the child to bed at a regular bedtime every night including weekends. The bedtimes should be set such that child gets at least nine hours of sleep every day for three months. Again, research is solid (see The Rested Child by W. Chris Winter, MD). Children benefit immensely from routine and from long, sustained, predictable periods of rest.

Third, ensure that the child gets three solid meals per day, the most important of which is a nutritious breakfast that does not include sugary morning snacks. Eliminate soft drinks and, to the extent possible, processed sugar from the diet. Enforce this rigidly.

Fourth, establish an after-school routine for the child which includes finishing homework when arriving home from school, doing all expected chores, and only then enjoying free-time. At a minimum, a half hour of outdoor play should be expected daily. Again, routine in this matter is important, so stick to it. (Note: New Covenant homework loads are designed such that they should not impede the implementation of this practice).

Parents who follow Keith’s advice and establish the baseline behavior for their “ADD” children return to his office and over 90% of them are completely disinclined to pursue medication for their children. A common report is, “Never mind the drugs; I have a different child than I did three months ago.” With the remaining 10% – those who now have a clearer baseline with a host of variables weeded out – he can then proceed to explore appropriate and fruitful treatment paths. For some, that may entail medication.

It should be strongly noted, however, that there are some underlying medical conditions that manifest the exact same symptom profile as ADD, but which have completely different causes. In those cases, ADD medications are completely ineffective and should not be prescribed.

If your family is struggling with a child who has symptoms of ADD, we invite you to consider professional care in baselining your child. It’s good to know that there are options other than medications.