Let me just say it and get it out of the way: there’s nothing wrong with STEM. Science, technology, engineering and math are all good pursuits. President Obama put out the call in his 2011 State of the Union Address, igniting a movement to teach students 21st-century skills to make them more competitive with other nations in the fields of STEM. Millions of dollars in funding from public and private sectors flooded in for teacher training, grants, research, and school programs that promote STEM study.

I make this honest confession because many believe that the low-profile that tech occupies in the average classical school belies a latent hostility to anything tech. This is simply not the case. We are suspicious, not because the pursuits are unworthy, but because STEM goals are very narrowly limited. Moreover, those limited goals may not be working as promised. There is growing evidence to suggest that STEM programs are no better at teaching math or science than non-STEM schools (Hansen, 2014).

That realization has induced what writers at edweek.org (2014) call a “tug of war” between STEM and STEAM. Advocates of the latter tell us to put the “A” back in there – the arts! A quick Google search will turn up any number of opinions about this. STEM advocates claim that the arts water down its core mission. STEAM advocates respond that STEM programs exclude huge numbers of students and the strengths they could bring to such programs.

And then there are the emerging voices for STREAM. What’s that? Put that “R” back in there; you know, reading! That would include literature and language. Critical thinking, they say, is not developed by merely asking a student to imagine how to get men to Mars, with a workgroup to problem solve the challenge. We grant that such an exercise might be engaging, useful and even educational. There are times to put students in situations with problems beyond their ability to solve. This does not, in itself make one a critical thinker. Critical thinking is the by-product of reading, writing, calculating, and playing an instrument. In other words it comes about through regular engagement across a variety of disciplines.

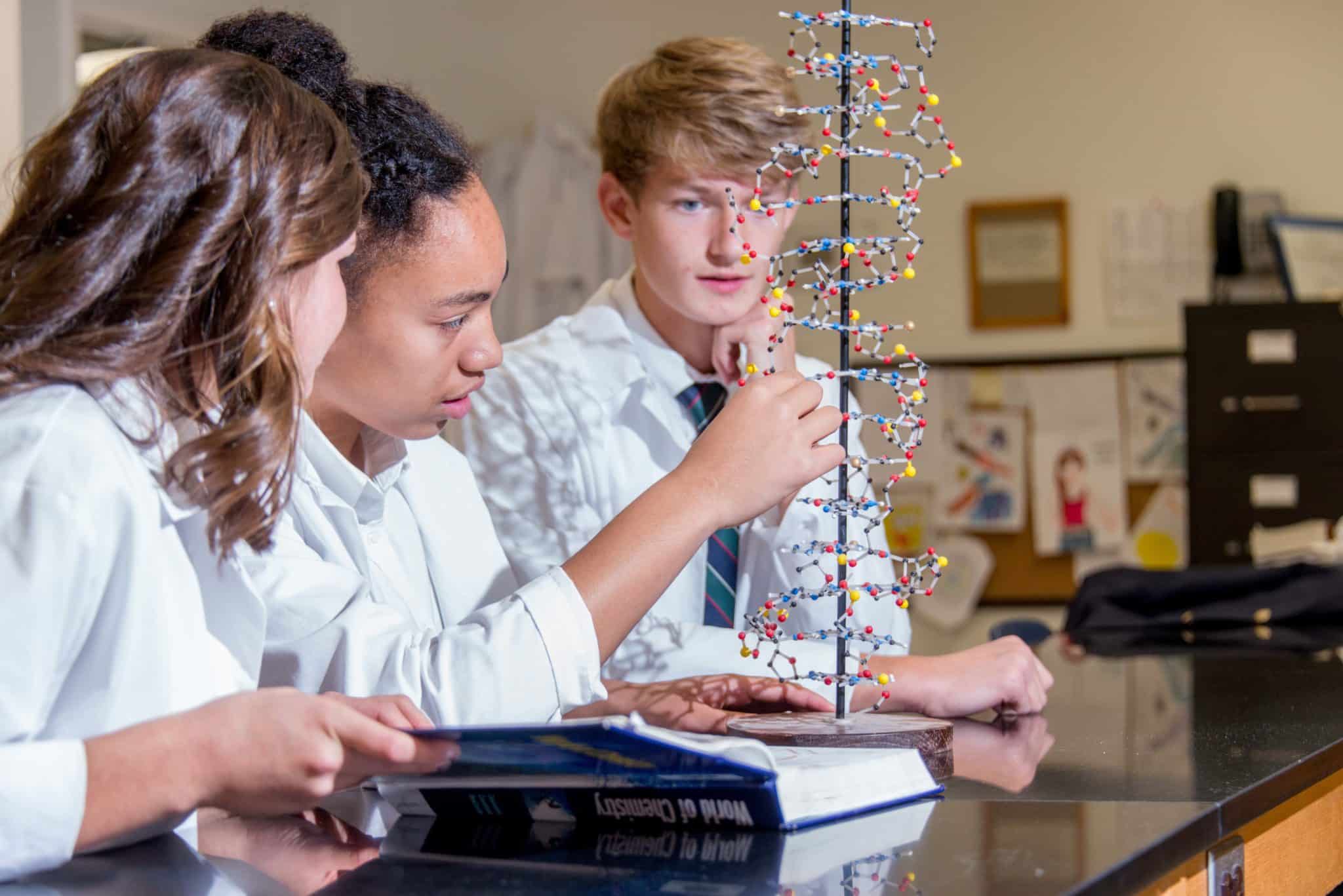

STEM? STEAM? STREAM? Which is better? You don’t have to choose. The classical curriculum includes – rather, it mandates – all three. The classical curriculum builds upon truth, goodness and beauty. Science and math are recognized pathways for discovering what is true and untrue about the material world. Theology, philosophy and literature are indispensable avenues by which we explore the spiritual and human realities of what is good or not good. Likewise, the arts – painting, drawing, music, dance, and theater – are ways of knowing the world, constructing knowledge, and figuring out how things cohere. It is the pursuit of beauty. The disciplines that flow under each of these broad banners are interconnected, and without all of them a student is underserved.

If you were designing a complete education, which would you eliminate? Would you drop the disciplines that guide us to know what is true or untrue? Forget about the books that explore the deep human questions that help us sort out and recognize the good? Or cut those classes that get in the way of 21st century problem solving because beauty isn’t necessary in our lives?

Are you kidding? It’s a false dilemma. I would no more consider eliminating music or art from the curriculum than I would math or phonics. Why? Art, like mathematics, provides a way of knowing the world. If it is not cultivated at an early age, a student is as deficient as if he had not been taught to read, add or subtract. Like language and math, art must be taught; appreciation for beauty must be learned. In short, the arts are an essential part of the curriculum for a student’s full development.

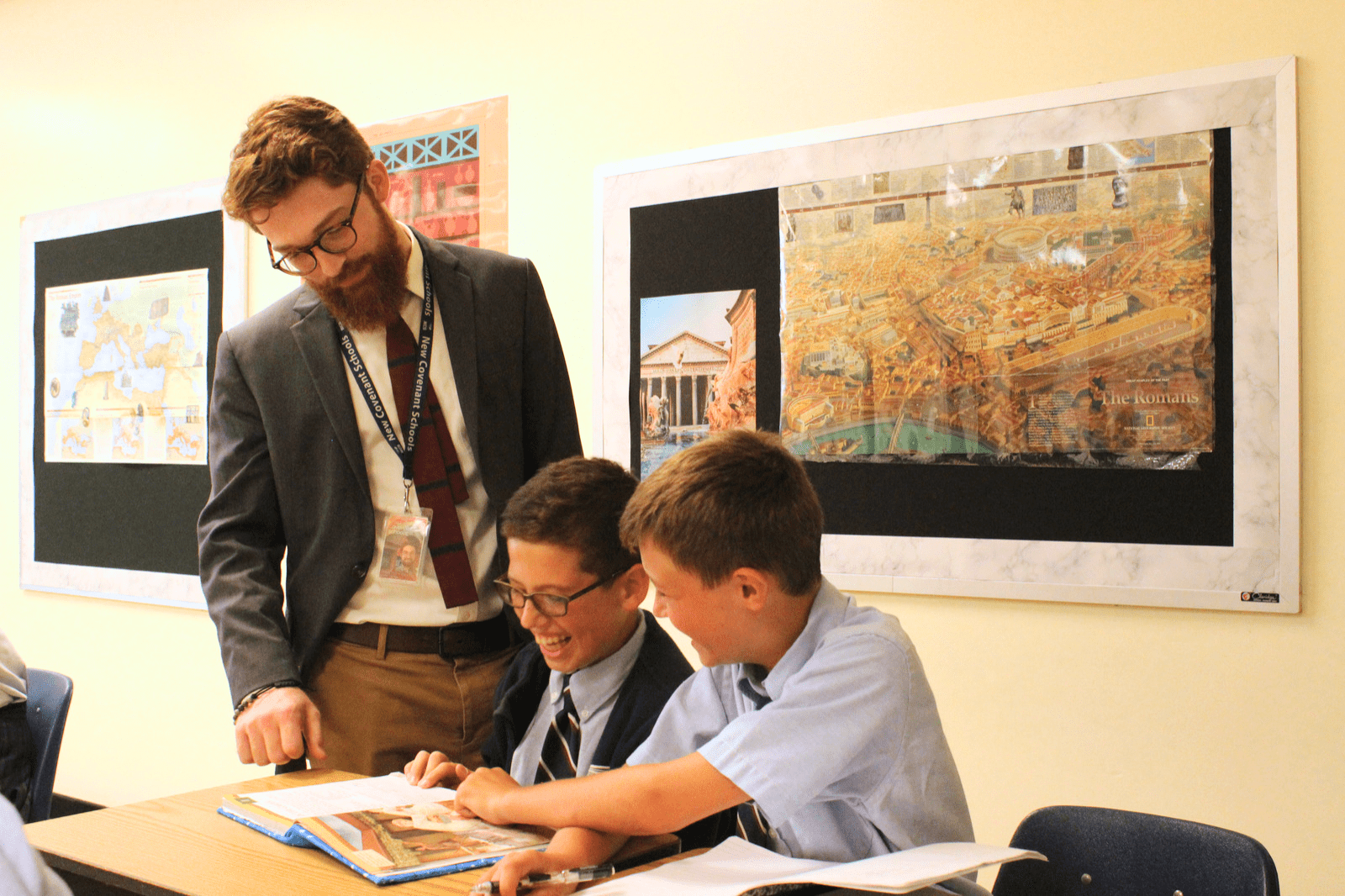

Classical education is a centuries old curriculum developed over hundreds of years of reflection upon what an educated human being looks like. Classical education engages the student broadly, not narrowly. We are constantly told that we are behind in 21st century skills. No, we are not. No one seems to know what 21st century skills are, and when I read those who try to explain them, the answers sound like the precise outcomes of a classical education: language skills of reading and writing, curiosity about the world (the mother of invention), principled, ethical character, and the deep knowledge that there is more to life than manipulating the material world or making money.

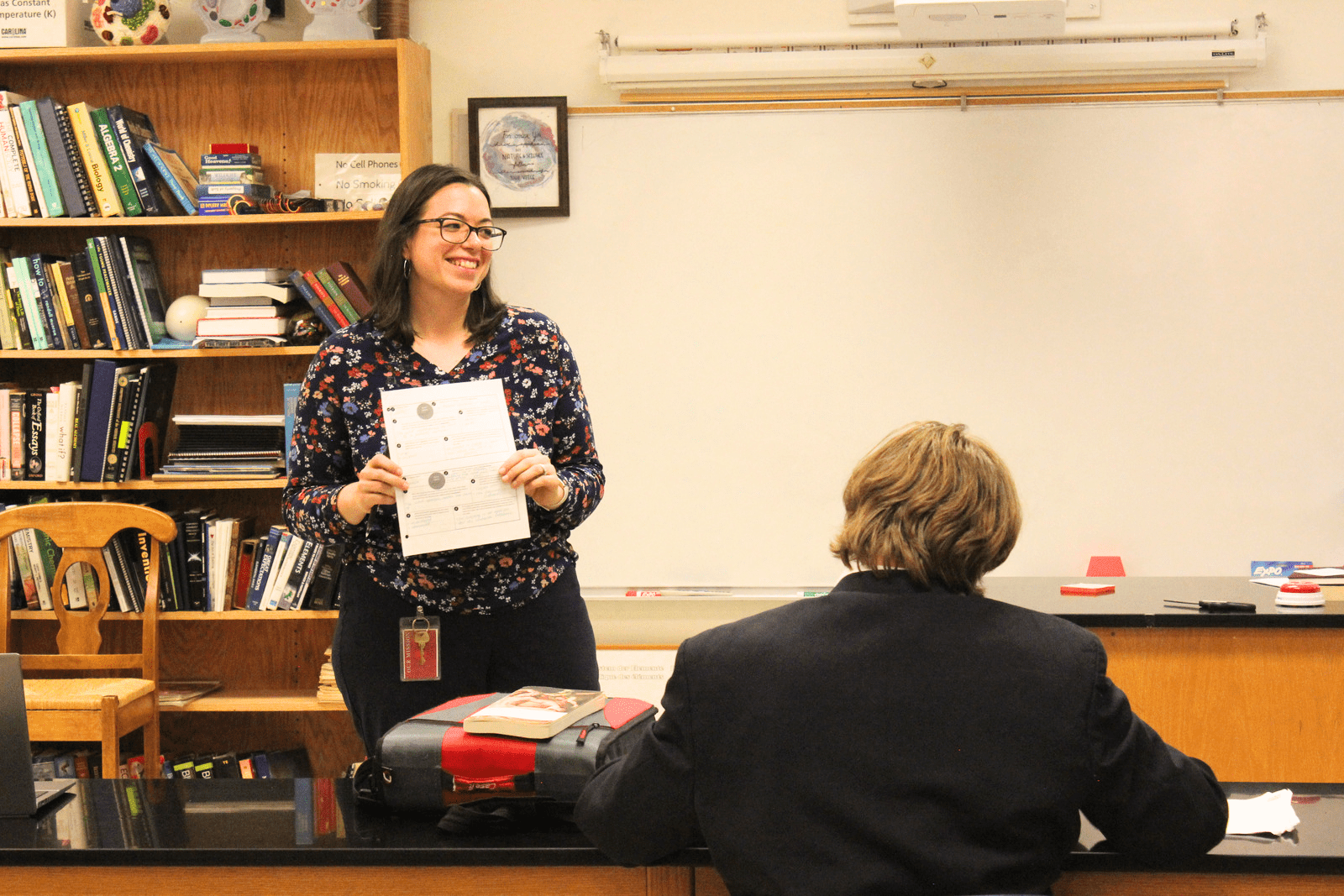

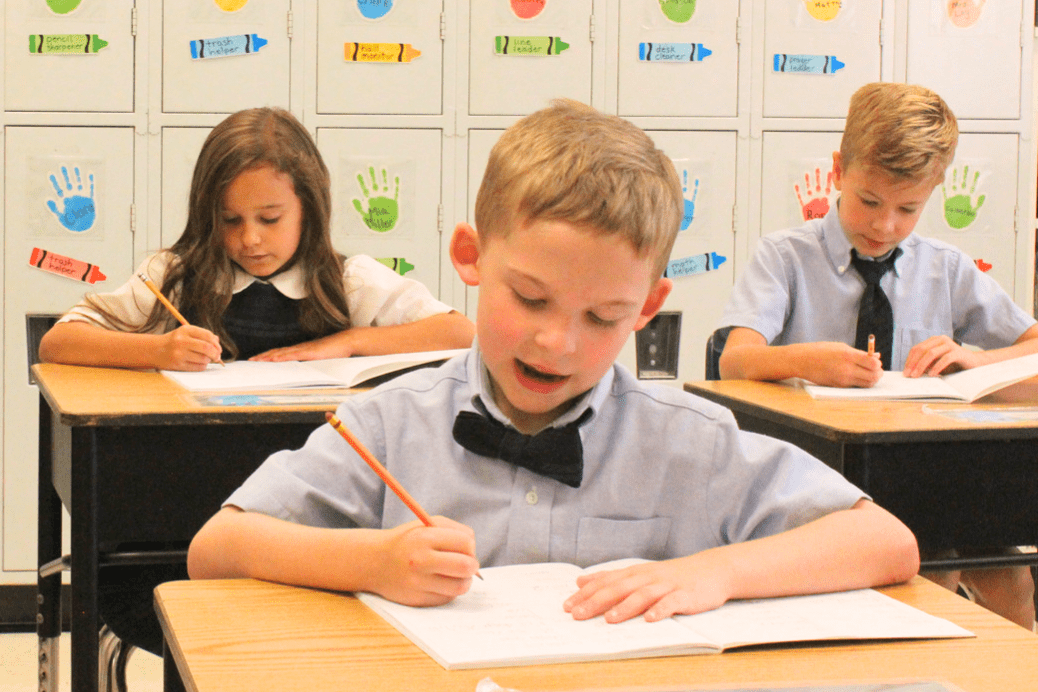

This is why all New Covenant students participate in the fine arts. That’s right. The arts are not optional. They are central. A classical education takes care not only to nourish the mind, but also the heart and the affections. We pay attention not only to truth, but also to goodness and beauty. Students who study music and art, and who participate in drama are broader in experience, and richer in the intangible sensibilities that only the arts provide. Every student who graduates from New Covenant goes into life with math, history, theology, science and literature. Every student from New Covenant also reads music, plays an instrument, or has experience with choral literature and theater.

Classical education is not satisfied with developing the narrow skills required by certain vocations that may be favored in our cultural imagination or politically popular. Rather it is totally human, offering a child the opportunity to explore the broadest horizon of interests that have captured the mind for hundreds of years. You don’t need to choose. A classical education offers all of it.