This blog was contributed by Dr. Erin Uminn, Principal of the School of Rhetoric. | The first time I toured the Library of Congress in Washington D.C. it took my breath away. Guests make their way through security, turn down attractive corridors, and finally spill into the large, open lower level. The eye is immediately drawn upward to the soaring, hand-painted ceiling and Corinthian columns that line the exposed second level. Italian and Tennessee marble form a checkerboard floor with brass inlay in a space built to rival the most spectacular structures of Europe. There are ornate carvings, grand staircases, relief portrait plaques of founding lawmakers, and an original Gutenberg Latin Vulgate at the entrance of the reading room, with its vast geometric dome. The message is unique—Biblical text, expansive aesthetics, the great ideas, and the building of a people is on impressive display.

Inscriptions are etched over doorways, including “What doth the LORD require of thee but to do justly, and to love mercy, and to walk humbly with thy God?” The interior is a striking reference to the living roots from which the nation sprung, incorporating famous ancient, medieval, and modern philosophers, statesmen, and theologians. One such quote is, “The foundation of every state is the education of its youth.” The Library contains tens of thousands of original documents and manuscripts. This is interactive education at its finest. In two weeks, our SOR students will take in the sights and sounds of D.C., and our 9th grade students will experience this impressive space.

Aristotle, the pagan philosopher who lived a few hundred years before Christ, opened his Treatise on Government by stating, “Every society is established for some good purpose—for an apparent good is the spring of all human actions—it is evident that this is the principle upon which they are every one founded.” It is this phrase—an apparent good—a life source for human action, that has me reflecting on the magnificence of the Library of Congress and its invitation to build. In the opening paragraphs of his treatise, Aristotle interestingly claims that society begins through the establishment of family through marriage. He did not start by expounding on the functions or laws of a state government. He began with the union of father, mother, and children. To form a society without that foundation, he claims, is to build upon sand.

From that comes the second association, which Aristotle terms “the village,” an “offshoot of the family.” Families associate and come from the same place or source—those who have grown together in the same region, language, and work. The final association is the collection of villages. This association, he claims, is the “height of full self-sufficiency” and that it “exists for the sake of the good life.”

It is here that we may reflect on the importance of formation, described in such documents as Jefferson’s Northwest Ordinance of 1787, which states, “Religion, morality, and knowledge, being necessary to good government and the happiness of mankind, schools and the means of education shall be forever encouraged.” If we go back even further to the Biblical account, the instruction to the Hebrews to love the Lord God is reestablished by Christ over a millennium later as the apparent good. The seismic shift of Christ’s ministry on the history of the world is found on every surface of the Library of Congress.

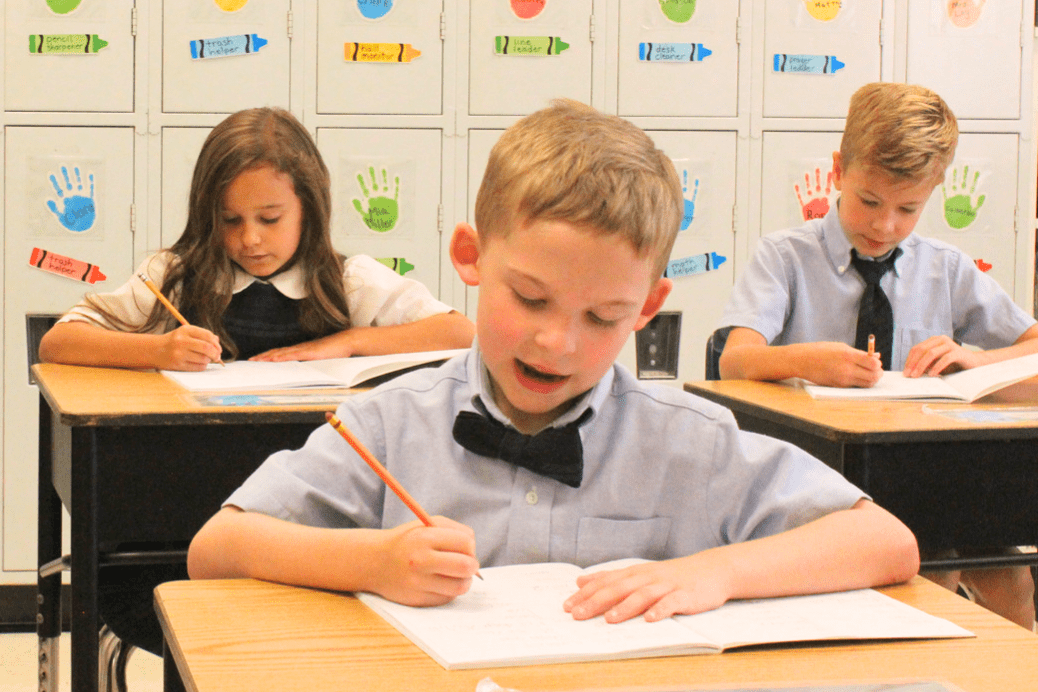

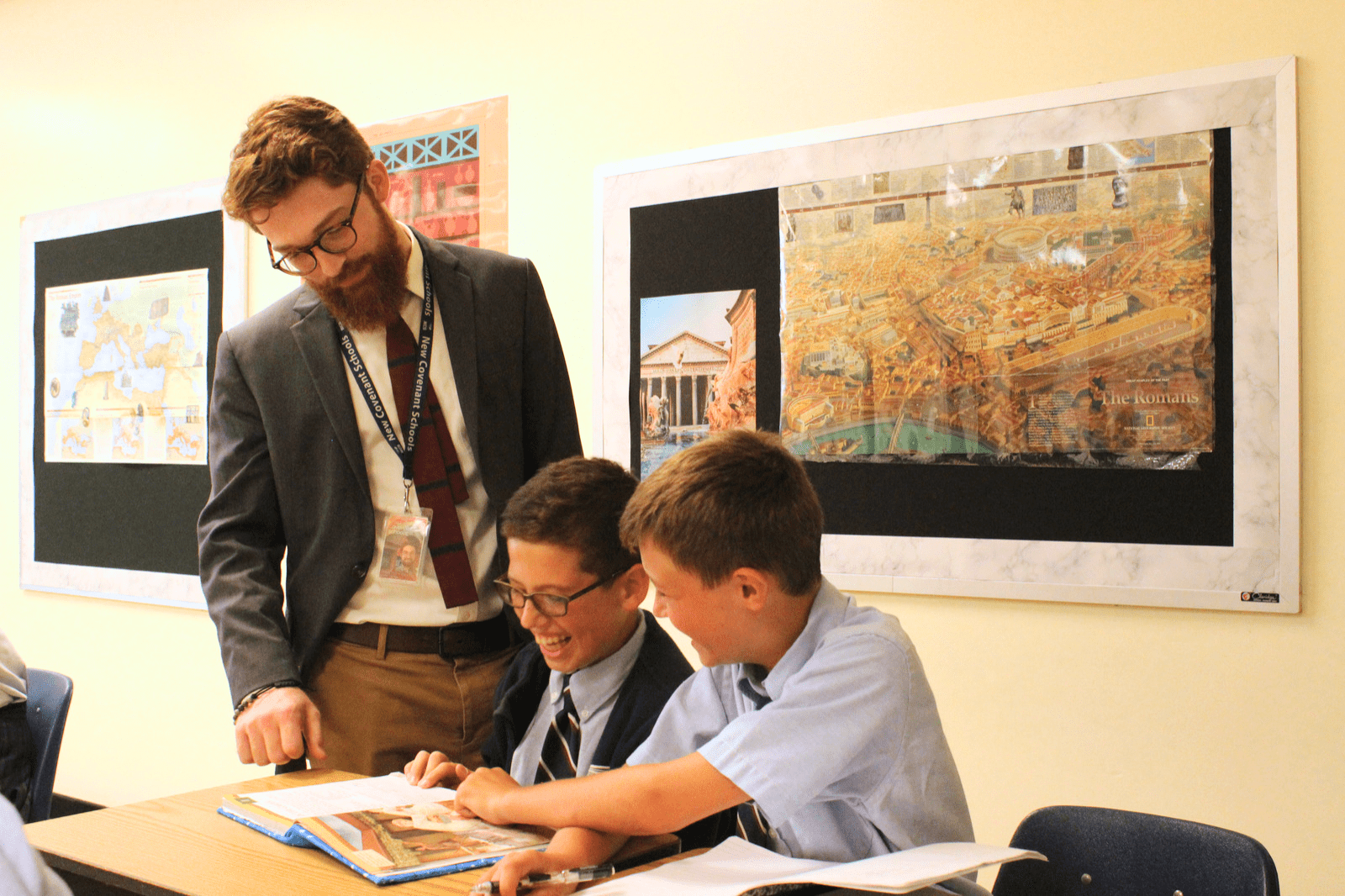

The faculty of New Covenant Schools is in the business of instructing souls, a village of second association after the family. There are basic competencies to expand the heart and mind of humans—reading, writing, and logic to unlock and to connect rather than isolate. It is to help students move outside of the dehumanizing idea that their only value is to adopt a function, earn money, and consume. Instead, we aim to combine the development of virtue through love and good works while steadfastly habituating to the discipline of lifelong learning. Humans become a reflection of how they have been built, just as the Library of Congress bears witness to the ideals that constructed it.

This is why we ask our students to wrestle with Milton and Dante, Homer and Virgil. It is why we ask them to slow down to write and speak. It is why we hold morning prayer and make space for generosity and service. It is why we put beautiful architecture, artwork, and words before them. They are image bearers of God, and an education rightly teaches them this fact. I would argue that we must do three things as the masons of our families, however small they start: Attend church, read and discuss essential questions and Great Books together, and model virtue. Here is how—find ways to set parameters and establish face-to-face interactions and participation around the family table, the neighborhood, the school, and church.

What is built into our hearts and minds is always displayed outwardly in our words and our deeds for the good or detriment of all, and this is especially true of Christians. When we ask students to consider, reflect, and take time, we do so to the betterment of their souls. We cannot make haste when instructing a child. The building of the Library in D.C. spanned more than seven years, but the collection of its contents took centuries. How much greater is the building of our children?

Photo by Lacza.