Part 3 of a series by John Heaton, Headmaster

In the twenty-five years from 1960 to the mid-80s, there was an explosion of Christian schools across the country. The first generation of these schools was often interested in segregation or in protecting children from the corrosive influences that characterized the 60s forward. Just over two decades into the project, it became increasingly clear that Christian schools needed to be more. In addition to their strong commitments to faith and morals, they needed academic credibility.

Those interested in the education of the young would not have to look far to find a model that would meet the test. They would find it in Dorothy L. Sayers. In the mid-20th century Sayers was an informal participant in a literary group of Oxford professors who called themselves the Inklings, the most well-known members of which were J.R.R. Tolkien and C.S. Lewis. In 1947 Sayers, a learned scholar who herself rendered a translation of Dante’s Divine Comedy, delivered a somewhat informal talk she called the “The Lost Tools of Learning.” It wasn’t intended to change the world, but it was a relatively short lecture that called for a return to classical education, the essence of the Western tradition. Even then she could see that it was being abandoned for more progressive ideologies, driven in America by the influence of John Dewey and others in the early 20th century. In discussing the “Lost Tools” she maintained that it was essential that students not just be told what to know, but—more importantly—how to think.

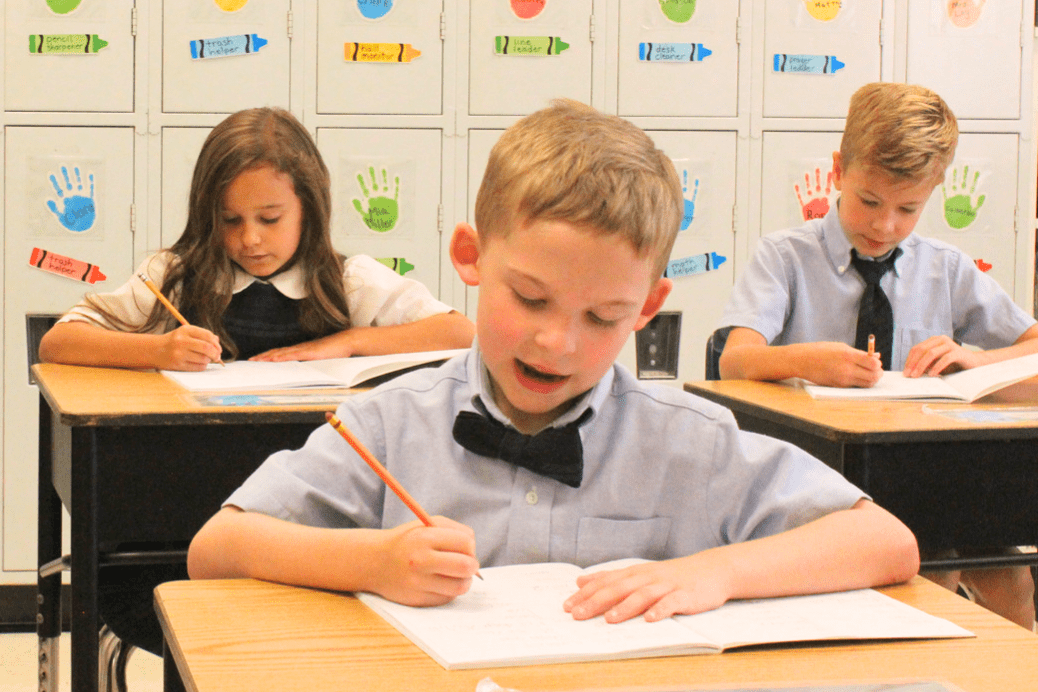

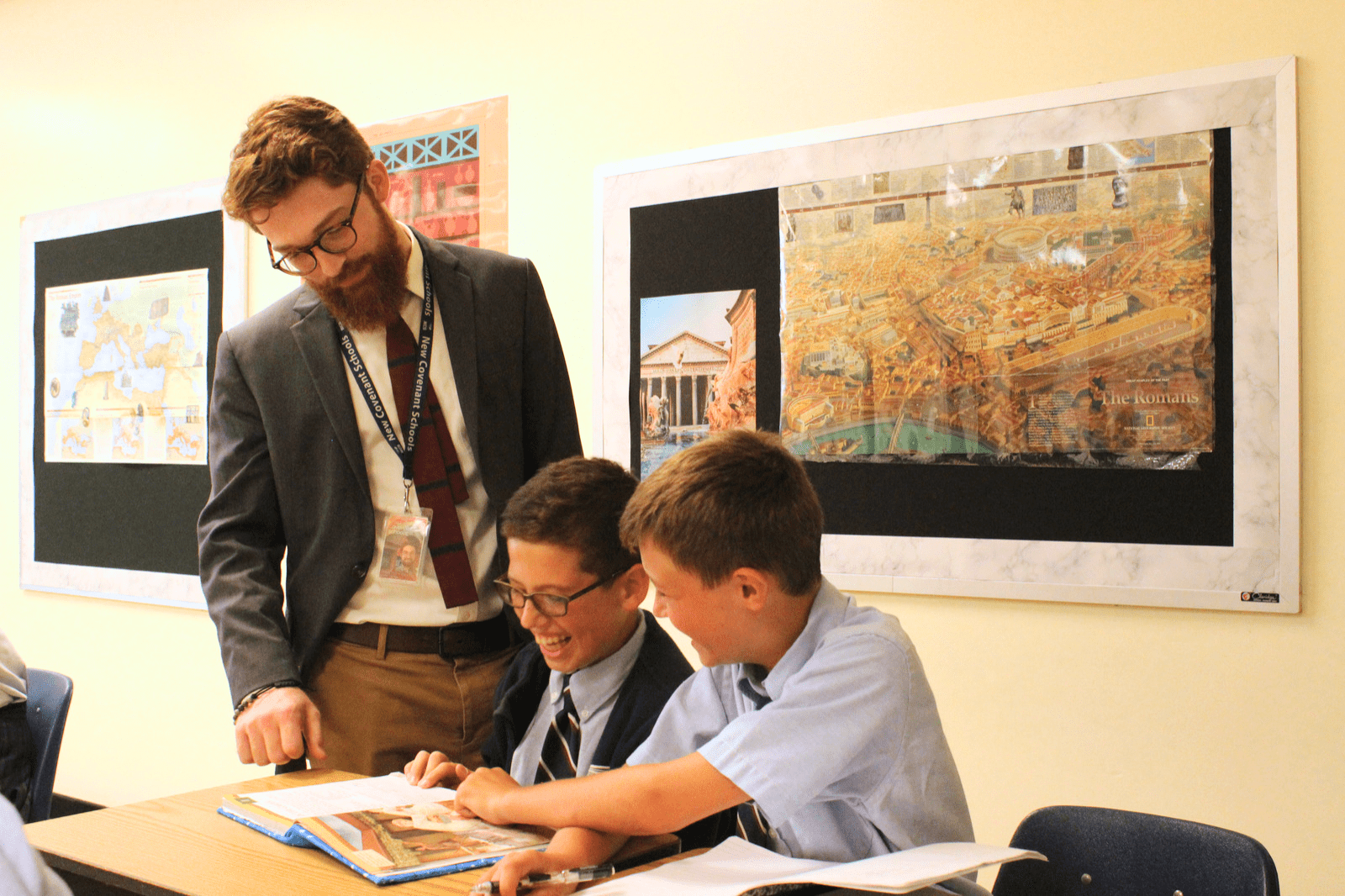

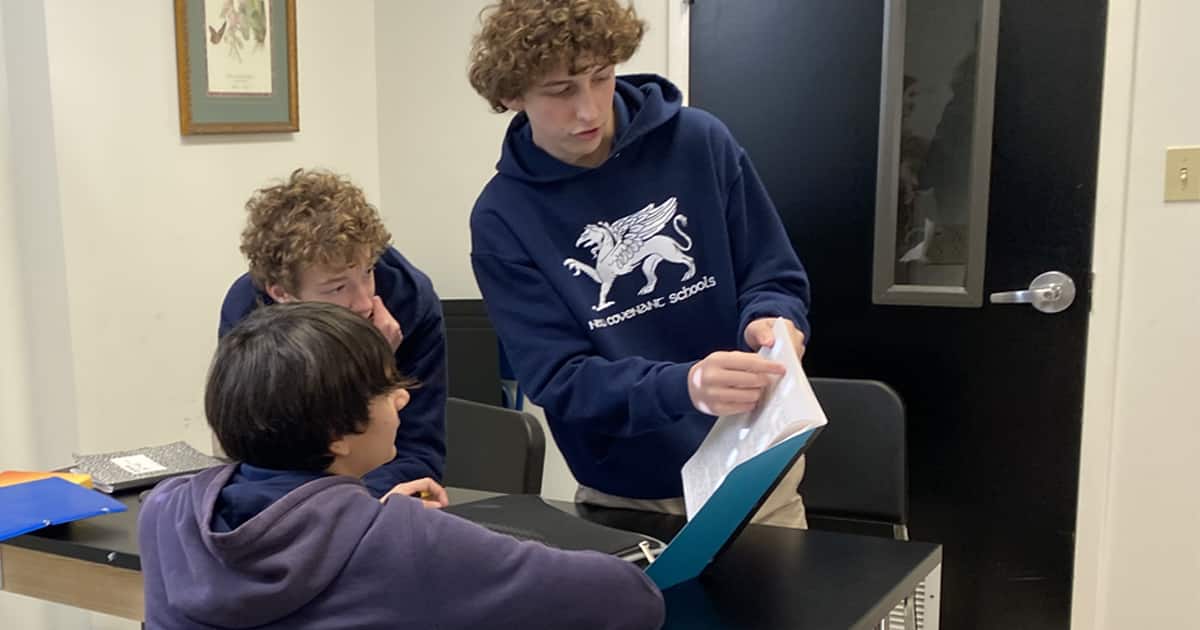

In the essay she identified what she called stages of human development that corresponded to the way children learn—grammar, dialectic, and rhetoric—and she pointed out that students were suited developmentally to each of these stages. We would prefer to call them “modes of learning.” In the grammar mode students were not averse to memorization of facts for their own sake—multiplication tables, lists of the Presidents, the states and their capitals, the kings of Israel, and, of course Latin paradigms. As students matured, however, they became naturally argumentative, so it would be commendable to introduce them to logic. If they were to be contrarian by nature, Sayers maintained, at least that tendency should not be permitted to run away into the sand. Finally, students in their mid-to-late teens should study rhetoric, which built on the grammar and dialectic of their education, and gave them the ability to express their own ideas with proper evidence, persuasion and grace.

Grammar, dialectic, and rhetoric—these were the tools that had been lost, but Sayers’ essay itself was unnoticed for more than thirty years, with the copyright eventually being obtained by William F. Buckley and the National Review. Sometime in the late 80s, it was rediscovered by Christian educators who found it challenging, and had the audacity to use it as a guide for recovering these “lost tools.” By 1991, a Presbyterian pastor, Douglas Wilson, had published a book under the title, “Recovering the Lost Tools of Learning.” The book was not only a severe critique of public education, but a positive expansion upon Sayers’ original essay. Incidentally, New Covenant Schools was founded that same year.

Neither Sayers nor Wilson was advocating anything new; quite the contrary. They were reclaiming a tradition that had been developed by the Church and field-tested for more than 1,500 years. It was classical because it focused upon classic texts, materials that had endured the test of time because of the universality of the questions they addressed, the fundamental questions of human flourishing. It was Christian because since at least the time of St. Augustine (d. 434) it was the Church that developed what came to be known as the liberal arts, which lay at the very heart of the curriculum. Here was a tradition that was both academic and Christian; in fact, it would not be an overstatement to claim that education in the West always had been Christian. Without the nurture of the Church there would never have been such a thing as the cathedral school or the university system as we know it.

In classical education, the Christian school movement of the late 20th century had finally recovered its original mandate. It is important to note that educators had not discovered a box of curriculum somewhere in the attic, discarded by generations of progressive educators. Classical education is not a specific curriculum. There is a remarkable variety of emphasis and content among classical, Christian schools. Moreover, classical education is not reduceable to a method; there is no such thing as “the classical, Christian method.” It is, rather, an approach, a way of looking at the world, a way of being. In its broadest objectives it is concerned with promulgating the best of that which has been thought and said by great minds of the past. It is helpful to think of it as a conversation into which we lead our students as participants. We introduce them to the primary languages of that conversation—Latin and Greek —and we introduce them to the great questions that have been the subject of this long discussion.

Of course, we begin with reading, writing, and basic arithmetic, but along the way students begin to learn the language of music, the language of math, and the language of persuasion. They are required to study art, which is yet another means of human expression. Broadly speaking, classical, Christian education will include as much as it can of all that is good, all that is true, and all that is beautiful. With these guiding principles, the classical, Christian educator creates a curriculum that stands apart from contemporary educational fads, and from the propagandizing of “woke” progressivism that currently dominates public education.

Read an edited version of Dorothy L. Sayers’ “The Lost Tools of Learning” here.