Exactly 30 years ago this month, 16 students had enrolled in the newest school in Central Virginia. It was called New Covenant, and for that first month the children were busy with lots of field trips because the curriculum that had been ordered late in the summer had not yet been delivered. The children gathered in a one-room school house, a small church, provided to them by the Reformed Episcopal Church. No one could have imagined what the next 30 years would bring.

The student body of 16 jumped to 65 the next year requiring a relocation to a larger space. The next year it jumped again, and again the year after that. By the time five years had elapsed, the numbers were nearing 150, and the school had moved three times. What was driving the interest? The same thing that continues to drive the interest 30 years later.

New Covenant was founded to recover and maintain a distinctive curriculum in the classical, Christian tradition. It was a new school founded on a very old idea. The program of instruction was built around grammar, logic, classical rhetoric, Latin, mathematics, and the arts and sciences. There was much more to it, of course, but these distinctives quickly separated New Covenant from other schools, not only by its faith tradition, but as a school that was serious about academics.

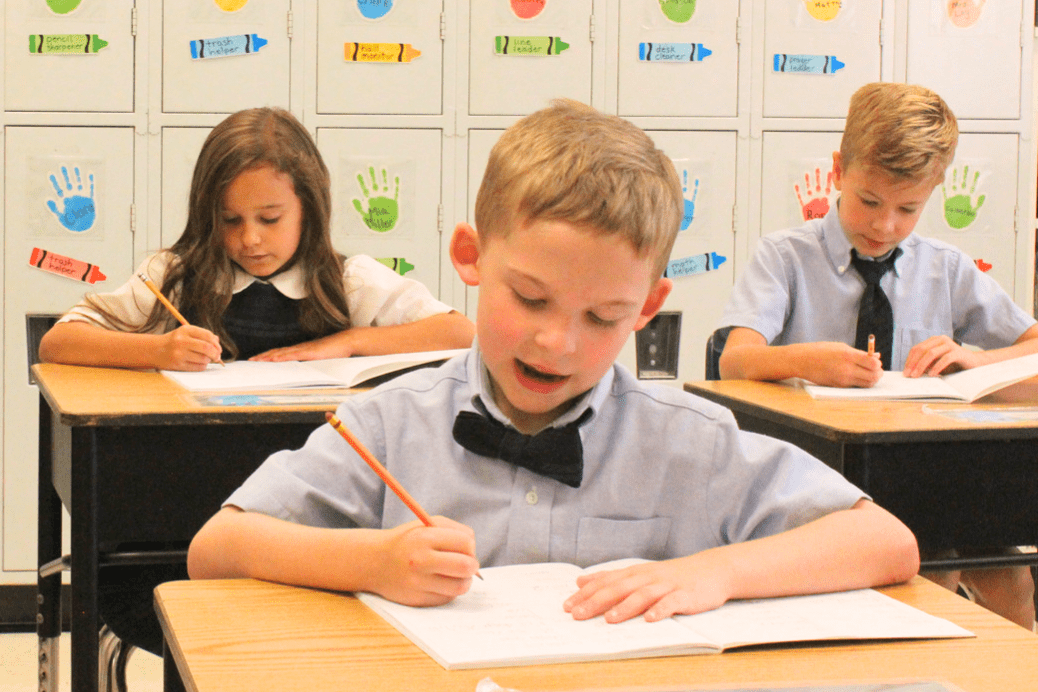

What makes classical, Christian education unique? We teach students not just what to know, but how to think. Young children enjoy acquiring facts for their own sake, but soon children want to know the “why?” and the “how?” A classical education indulges such questions and makes the pursuit of knowledge mandatory. There are four keys to achieving a superior education.

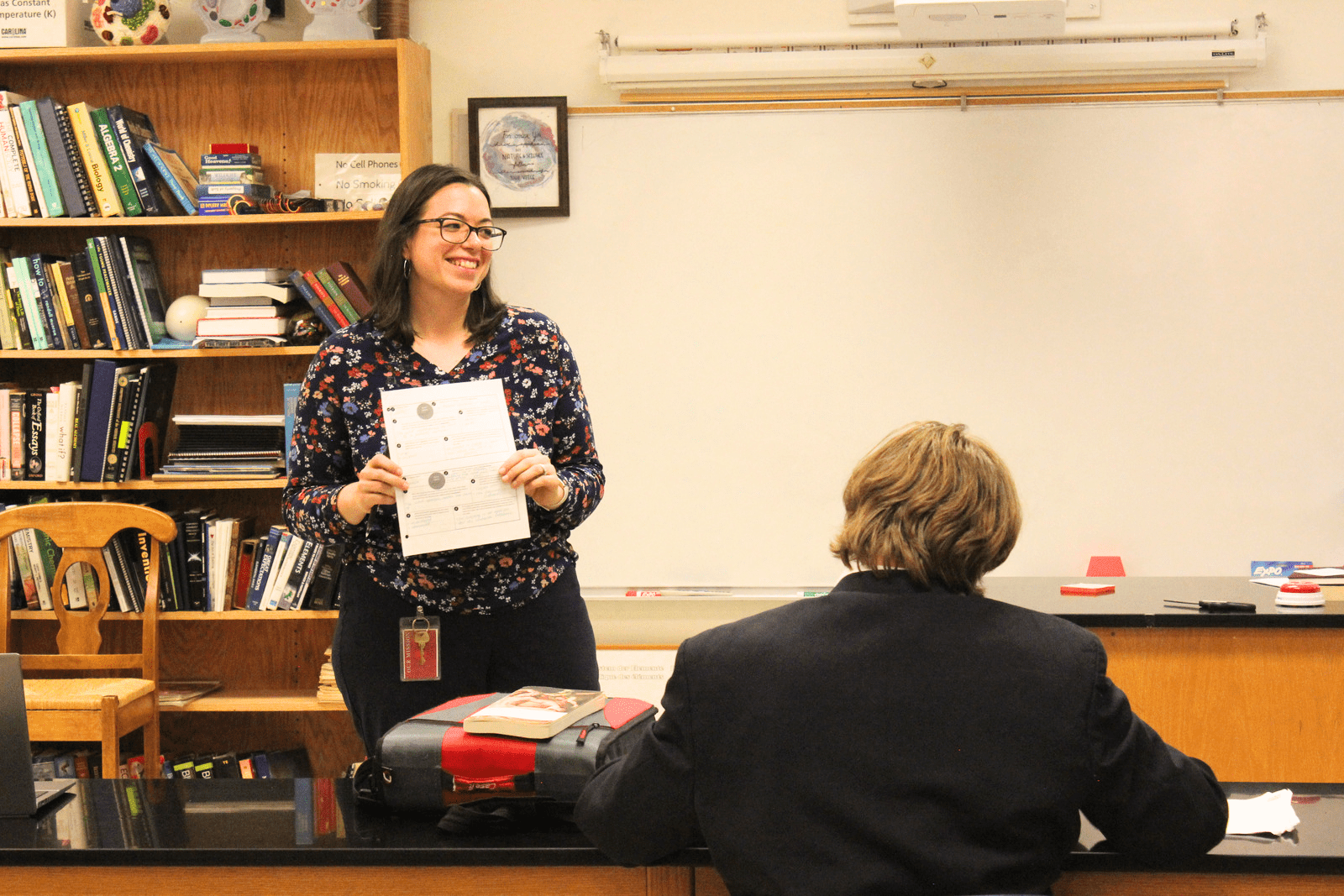

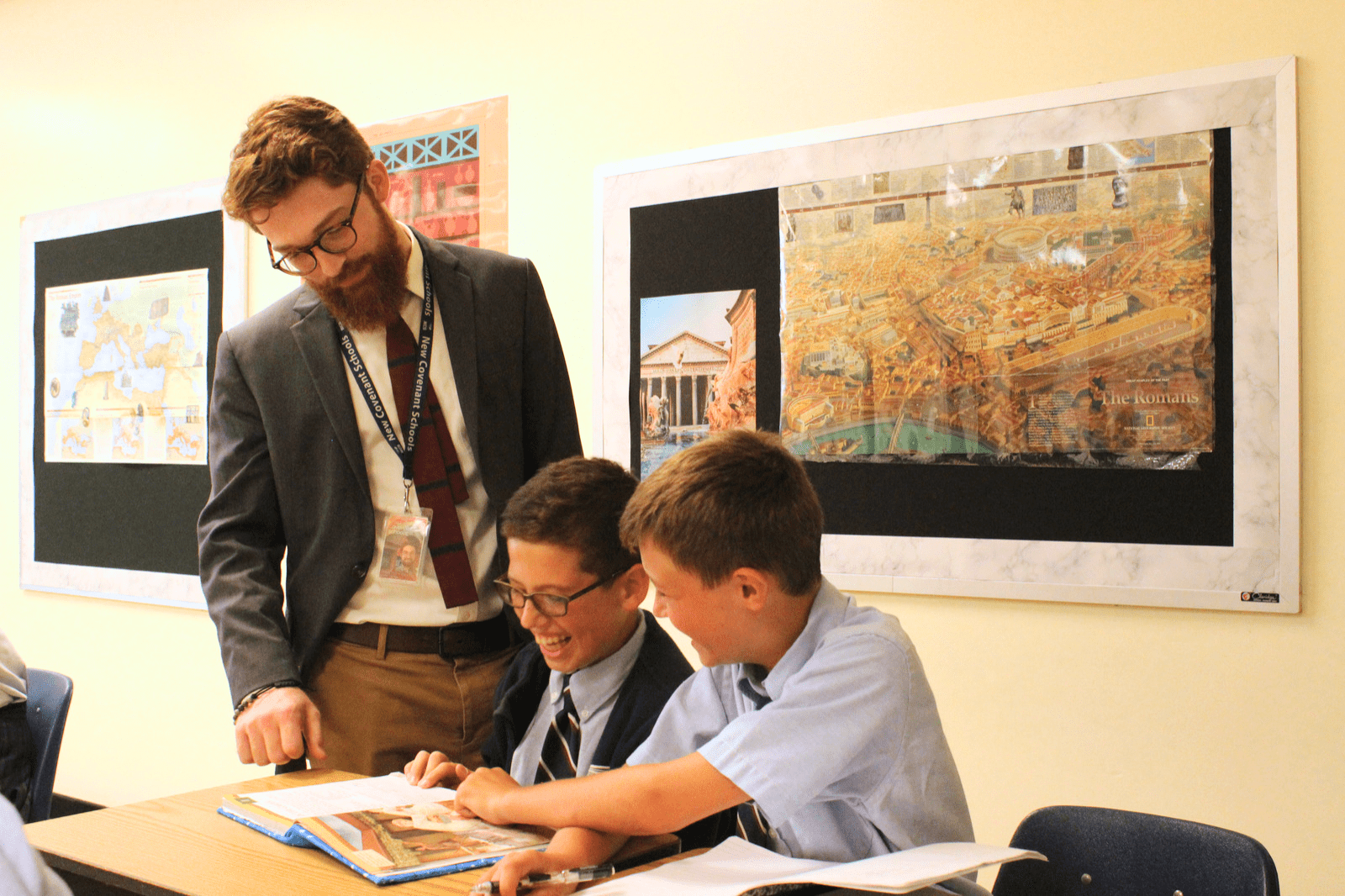

First, there is the mode of direct teaching or lecture. Teachers use this mode when students are introduced to new information they have not encountered before. Classrooms are teacher- directed, not student-centered, and the focus is upon the knowledge of a master teacher, and the authority that entails. The mode of lecture in the hands of such a teacher is used intentionally for a specific purpose. An effective teacher lectures with organized thoughts and at a sufficiently slow pace to provide time for absorption, for questions—not full reflection, but for acquisition of the concept at hand. Sensing the “aha” moment, the effective lecturer will know exactly when to conclude. Lecture is then combined with other forms of active learning, and is the very definition of good pedagogy.

Second, there is the mode of reading. New Covenant students read constantly and they read together. It is not unusual to walk into a class at random and find the students reading with their teacher. Reading a book together is like listening to music. We allow it to proceed at its own pace, not demanding that we understand it as it goes. The most important thing is the experience itself, with analysis following afterward, not unlike what we do when we watch a film or a play. Because we read “real books,” the teacher is a necessary part of the process, guiding, explaining, directing and entertaining new thoughts.

Third, there is the mode of writing. Our students write more than those in any comparable school in the area. Daily writing enables participants to encounter their own intellectual and imaginative responses to material studied in class. Writing is a “making of meaning” rather than a report of thought that has already been done. Informally jotting down ideas in a Commonplace Book (all students in high school keep one) is a way of liberating the imaginations from the constraints of formal writing. We do that, too, because editing and reflecting are necessary for effective writing. Both make up part of that formulation and clarification of ideas for which the civilized mind strives. It is no wonder that our students are universally overprepared for college writing. The end result of constant reading and writing is a discriminating mind, an eye for imagination and detail. In short, it produces critical thinking.

The final mode is the mode of seminar. Late in the middle school years around grade 8, our students are introduced to the art of discussion. They are seated in a circle or at a table with a text before them (one that ideally has been read before), and they are shown how to discuss it. In the School of Rhetoric, the name for this is the Harkness method, and, when it begins, no one knows where the discussion will actually go or how it will develop. This is not a mere sharing of personal opinion; at its best, it is a disciplined exploration of one another’s thought. The text is the main focus, and development proceeds through dialogue with the ultimate aim at consensus. Sometimes that is reached, sometimes not. The process, however, teaches students how to get at knowledge through the civil exchange of ideas.

After 30 years we still feel like the “new school” in town. Truth be told, we’re not doing anything new at all. New Covenant has returned to the oldest tradition in the history of the world, with time-tested content and methods. Our resistance to educational fads and the low standards that often accompany them is what drives the demand for the classical, Christian curriculum. After 30 years of practice, four capital campaigns to develop a distinct campus, and hundreds of students later, these four modes of teaching remain unchanged: lecturing, reading, writing, and seminar. Willing students who engage with the classical, Christian tradition will graduate ahead of their peers, and will be well on their way to becoming educated and civilized human beings.