by Jeremiah Forshey

Jeremiah Forshey is a faculty member in the School of Rhetoric where he teaches literature and senior thesis.

When my youngest son James was three, he played games hosted on an educational website to help him learn the sounds that letters make. The games were bright and colorful and fun, and they did a good job teaching what they set out to teach. But as I watched him play one afternoon, I realized that they were teaching him something else, too—something that had nothing to do with phonics and everything to do with his fundamental disposition toward the world. At the end of each short interactive animation, a chipper  voice would ask, “How did you like this story?” and three colored faces would pop up: a green smiley face, a yellow neutral face, and a red frowny face. Three-year-old James was learning that his most authentic interaction with this vast new world in which he found himself was the gut-check, that he should expect his immediate impression to be solicited and valued, and that the world should change to accommodate his tastes: if he chose the red frowny face, the chipper voice promised, “Ok! We won’t play this story anymore.” In short, little James was learning to be a consumer.

voice would ask, “How did you like this story?” and three colored faces would pop up: a green smiley face, a yellow neutral face, and a red frowny face. Three-year-old James was learning that his most authentic interaction with this vast new world in which he found himself was the gut-check, that he should expect his immediate impression to be solicited and valued, and that the world should change to accommodate his tastes: if he chose the red frowny face, the chipper voice promised, “Ok! We won’t play this story anymore.” In short, little James was learning to be a consumer.

The consumer is an autonomous chooser: his will is sovereign; his taste is the measure of all things. It struck me as I watched James that there are myriad ways our society silently catechizes its children: “The chief end of man is to choose what he wants and enjoy what he likes.” While the consumer mentality might be a good way to buy yogurt or select an insurance policy, it makes it impossible to receive art, to enjoy nature, to worship God, or to do any number of other things deeply important to human flourishing. Of particular importance to us, a consumer mentality undercuts the entire project of classical Christian education. In his seminal little book on education, The Abolition of Man, C. S. Lewis says,

Until quite modern times all teachers and even all men believed the universe to be such that certain emotional reactions on our part could be either congruous or incongruous to it—believed, in fact, that objects did not merely receive, but could merit, our approval or disapproval, our reverence or our contempt.

St. Augustine defines virtue as ordo amoris [“the ordering of love”], the ordinate condition of the affections in which every object is accorded that kind and degree of love which is appropriate to it. Aristotle says that the aim of education is to make the pupil like and dislike what he ought. (25-26; Ch. 1)

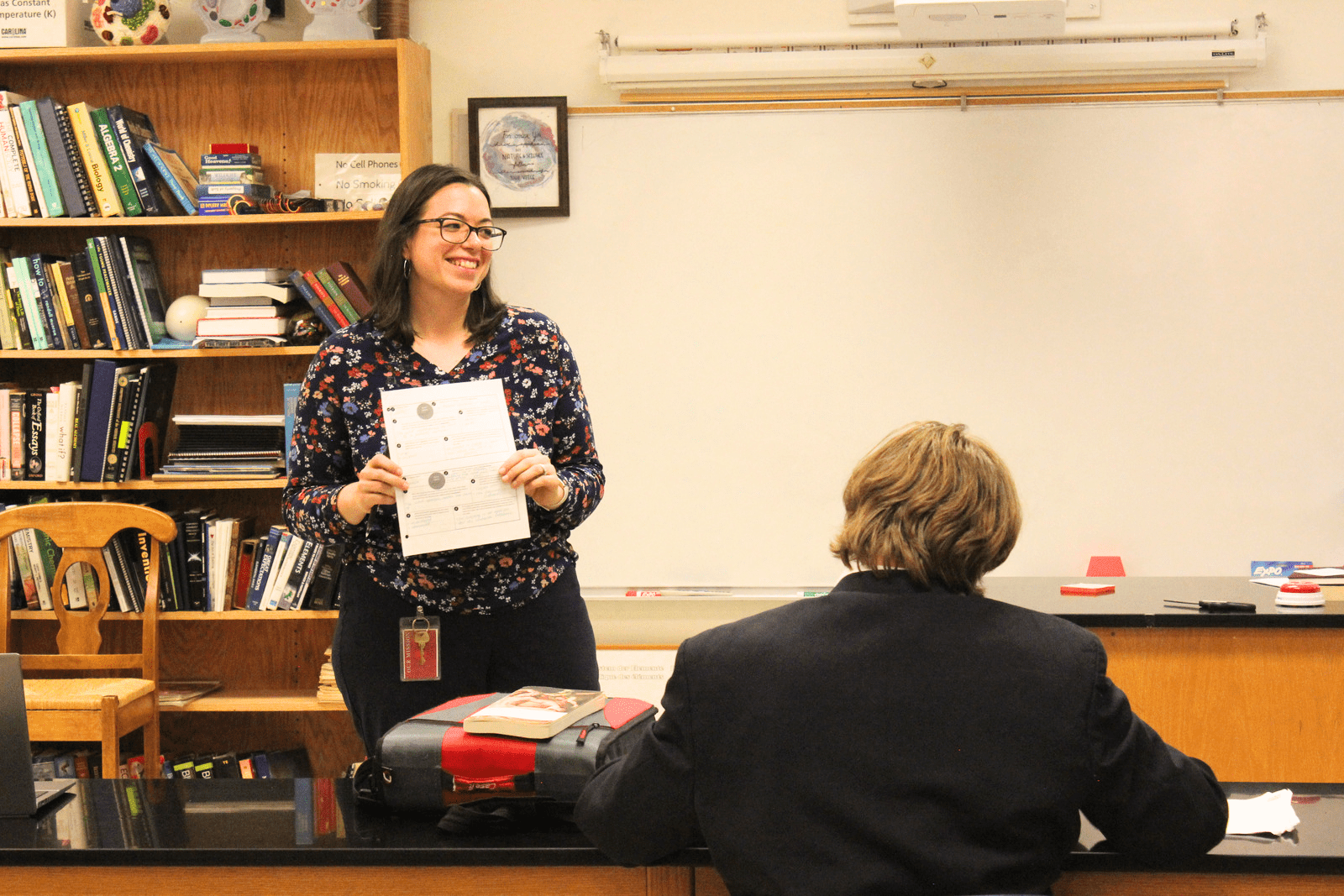

The consumer mentality asks what the child prefers so that it can shape the world to match what he likes. A classical Christian education wants to shape what the child likes to match the world, especially the moral and artistic world. It holds that our likes and dislikes can be appropriate or not to moral values and beautiful things, and our task as educators is to nourish the right affections, to rightly order the loves. “Hate what is evil and cling to what is good,” St. Paul tells us. But by the time little James gets to my literature classroom, he has already been shaped by sixteen years of that imperceptible tectonic movement by which culture is transferred. He comes with a bone-deep confidence in the importance, perhaps even the sanctity, of his own preferences. He lacks a habit of humility and patience before something greater than himself, something which will not be forced to reveal its beauty without time and attention. Barring our intervention, that is. Our task, therefore, is to foster habits of humility and gratitude, to reinforce for children the givenness of the world—the understanding that God’s richest blessings are not selected, but can only be either received with gratitude or received with grumbling.

One practical way to do this is to reframe the questions we ask our children, positioning them not as consumers reporting satisfaction, but as recipients of bounty. For example, there’s a popular conversational game parents play with young children at the end of the day called “highs and lows.” The child is supposed to tell one thing they liked from their day (a “high”) and one thing they didn’t like (a “low”). While I see the advantage of this game over the dead-end question, “how was school today?”, it once again invites young children to be consumers, to measure the day’s events against their juvenile preferences, to use an unreflective gut-check to process their experiences as “likes” or “dislikes.” It encourages self-absorbed and critical answers. (High: “I got to be line leader today.” Low: “The teacher didn’t call on me even though I had my hand up first.”) Perhaps the six year old presuming to stand in judgment over his teacher would be a teachable moment at home, but my own experience as a parent makes me wonder how often such complaints are met with some version of the red frowny face’s chipper apology: “Ok! We won’t play this story anymore.”

Better questions could achieve the same conversational goals of “highs and lows” without repeating once more the liturgy of consumerism. “What are you thankful for today?” or “What was the coolest thing you learned about today?” give a specific prompt without inviting a consumer response. Asking “How were you a good friend today?” reminds children that they aren’t just passive recipients, but they too have obligations to others; and it gives parents a chance to praise and reinforce some small act of kindness. Children do need to feel comfortable talking about negative experiences, but “Did something make you sad today?” would allow that where necessary while not inviting petty critiques about running out of chocolate milk or how boring the science lesson was.

One of the goals of a classical Christian education is that by comparison with a tradition longer than his present moment, the student would be aware of those areas where his culture is in tension with his Christian faith. One such area is our deeply ingrained habit of seeing all the world as a marketplace and ourselves as consumers. We must instead train our children in habits of humility and gratitude, to better equip them to perceive beauty and receive truth.